Note: This entry was originally posted on a blog I created for my History of Medicine class final project during December 2012.

Due to its relatively late emergence as a defined field in the United States, emergency medicine is often described as "new". This foundling status is sometimes used as a reason why professionals in that field perceive discriminatory pay and status compared to other medical fields that have apparently existed for much longer. However, truth be told, emergency medicine reaches much back farther than the 1960's paper credited with establishing EMS in the United States. This history is so lengthy, in fact, that it would be impossible to reasonably cover it in one blog post.

After all, as long as there have been wars, there has been a need for emergency medicine in one form or another; what's more, one could divide emergency medicine into the two components of transportation and treatment. Therefore, one could reasonably classify all wound treatments as EMS; then EMS might be considered the oldest of all the medical specialties, laying claim to figures like Galen. However, modern EMS is connotatively inseparable from its transportation aspect, so I'm going to mainly consider this. To that end, I'll go over a few interesting cases that should prove that even with strict application of this designation, EMS has roots far back in time. (This two-edged definition is perhaps what makes the history of EMS so difficult to trace. Should both emergency treatment and transportation be required of an event in order to link it to the background of EMS, or is it okay to focus on only one of those factors? The first approach is too narrow, yet the latter ends up being too comprehensive. Where do we draw the line?)

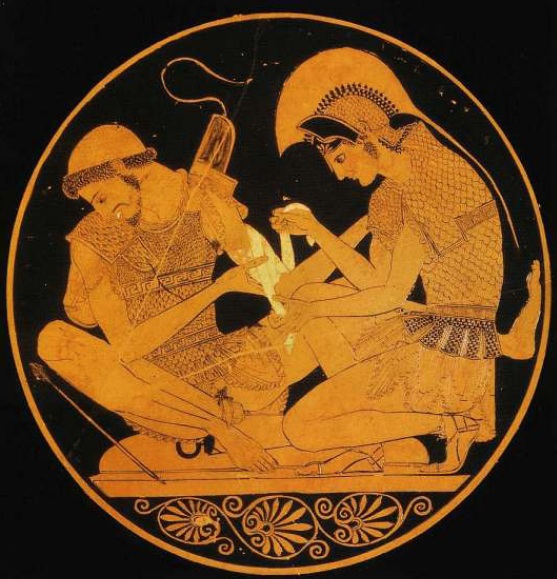

Greek & Roman. As early as Roman times, chariots and carts were used to remove injured soldiers from the battlefield. Nobody knows if these carts were specially equipped or if there were individuals assigned to provide rudimentary treatment. Initially, these soldiers were probably simply deposited out of harm's way; by 100 AD, they would be taken to valentudinaria, or Roman military field hospitals. Sometimes, however, before or instead of transporting a fallen soldier, care was simply administered on site, occasionally even while the battle raged on. One ancient Greek vase depicts the story of Achilles bandaging the arm of his wounded cousin (Robbins).

1000-1500 AD. In 1080, the Brothers of the Benedictine Monastery of Saint Mary Latina founded a hospital in Jerusalem to provide medical care for pilgrims to the Holy Land. This group would eventually become the Knights of St. John and would assist in the Crusades, evacuating and providing treatment for injured soldiers. Their symbol, the Maltese Cross, is in use today by fire departments everywhere. According to Robbins, "It is one of the first validated examples of what could be called in today's terms, a regional EMS system, incorporating the basic elements in detection, response, assessment, treatment, transport and definitive care." However, the first recorded use of the ambulance -- strategically defined here as a vehicle dedicated exclusively to the transport of the injured -- as occurring under Queen Isabella's direction during the Granada War, fought 1482-1492 (Bell, Robbins). It was during this war that the term "ambulancia" first appeared, referring to mobile tent hospitals that could be quickly moved about to meet the needs of battle. Special bedded and covered wagons were appointed to collect wounded soldiers and bring them to the tents. Yet, although other countries in the era started to take notice of this technique, ambulances would largely fall to the wayside for centuries (naturally, emergency medical treatment would always remain in vogue, but organized systems for moving the hurt fell out of focus). Bell blames this lack of enthusiasm on a perceived lack of utility; the ambulances did not seem to increase survival rates, and so were not popular.

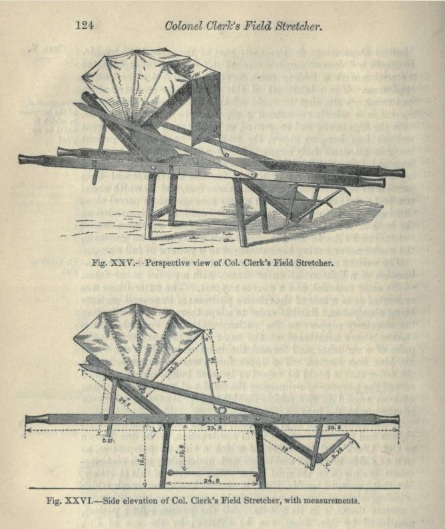

The Napoleonic Wars. By almost all accounts, Dominique-Jean Larrey, a surgeon in Napoleon's army, revolutionized the stagnant ambulance industry. According to Ortiz, prior to the widespread use of gunpowder, most soldiers would treat their own wounds, and only after several hours, after the battle had ended, might they hope to be looked at by a doctor. However, the widespread and devastating injuries inflicted by gunpowder-powered weapons rendered this model unfeasible, and gunfire provided the impetus for a better EMS system. In 1792, Larrey wrote:

I now first discovered the inconveniences to which we were subjected in moving our ambulances or military hospitals. The military regulations required that they should always be one league distant from the Army. The wounded were left on the field, until after the engagement, and were then collected at a convenient spot, to which the ambulances speeded as soon as possible; but the number of wagons interposed between them and the Army, and many other difficulties so retarded their progress that they never arrived in less than 24 or 36 hours, so that most of the wounded died for want of assistance...this suggested to me the idea of constructing an ambulance in such a manner that it might afford a ready conveyance for the wounded during battle. I was unable to carry my plans into execution until some time later.

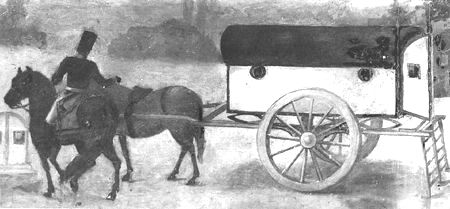

Larrey determined that a horse-drawn vehicle would work best, and designed a relatively light and nimble vehicle, which he termed the "flying ambulance", that could quickly dart in and out of the battlefield, which he described as follows. Larrey also focused on patient experience by using swinging sashes that provided relatively comfortable rides compared to hard wooden floors.

The frame...resembled an elongated cube, curved on the top: it had two small windows on each side, a folding door opened before and behind. The floor of the body was moveable; and on it were placed a hair mattress, and a bolster of the same, covered with leather. This floor moved easily on the sides of the body by means of four small rollers; on the sides were four iron handles through which the sashes of the soldiers were passed, while putting the wounded on the sliding floor. These sashes served instead of litters for carrying the wounded; they were dressed on these floors when the weather did not permit them to be dressed on the ground.

However, more than simply raising an idea for the ambulance, Larrey created a system for running them, utilizing hierarchical rank of regularly trained soldiers dedicated to manning the vehicles and providing for the injured. Here, we get a great example of an ambulance that not only transported but also treated; officers that accompanied the ambulance carried other instruments and kept dressings in their pistol holders so that they could provide aid on the go. As a result of his ambulance corps, Larrey was able to improve amputation survival rates. Unsurprisingly, the flying ambulance quickly gained the esteem of his colleagues, commanders, and even Napoleon himself, who quickly implemented it throughout his armies. In fact, Larrey's model would later provide inspiration for the United States military to use helicopter evacuations for its wounded in the Korean and Vietnamese conflicts. However, other nations were relatively slow in adopting Larrey's brilliant techniques.

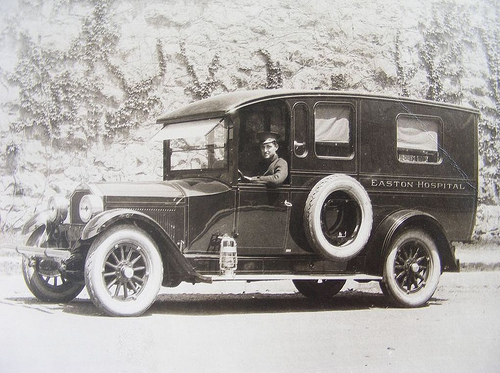

The Civil War. Physician Jonathan Letterman might be considered the Larrey of the Civil War when it comes to ambulances (indeed, today many call him the "Father of Battlefield Medicine"). American soldiers were often left to the fate described decades earlier by Larrey: abandoned on the battlefield, festering with their wounds long after fire had ceased. In some cases, removing the injured took up to a week; in the face of such horrifying circumstances, General McClellan authorized Letterman to do as he pleased to address the problem of the wounded. Letterman wasted no time and started an ambulance corps similar to Larrey's, appointing soldiers to collect the injured and bring them to first aid stations using horse-drawn carriages. In the Battle of Antiem in 1862, fighting left 23,000 Union soldiers dead, but ambulance personnel managed to remove all of the wounded within 24 hours. Letterman's higher-ups approved of his system just as much as Larrey's higher-ups had, and in light of its successes, in 1864, Congress officially adopted the system for the US Army. Shortly thereafter, in 1865, the first official civilian ambulance service started out of a hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio. (Another EMS landmark would occur soon in 1877, but this time across the ocean; the St. John Ambulance Association, which is still in operation today, would begin tending to Britain's sick.)

Conclusion. As I have shown, EMS as an entity that transports and treats the ill is far from, with roots that go back centuries. However, I've merely exposed the tip of the iceberg. The number of governments and military professionals calling for better ambulance services in the late 1800s is almost mind-boggling, and the curious reader could spend hours discovering such documents and days or months reading them. Take for example, Longmore's 1869 Treatise on the transport of sick and wounded troops, in which he highlights severe shortcomings in the British military's dealing with such (he would write a manual on ambulance operations almost thirty years later). While it's true that EMS in the United States has always been a step behind than that of other countries, it's simply absurd to draw its starting line as the 1960's.

History of EMS Timeline

This timeline is borrowed from NHTSA instructional guide and contains events that said governmental body feels important to the history of EMS; I have added links to relevant explanatory content.

EMS Prior to World War I

- 1485 – Siege of Malaga, first recorded use of ambulance by military, no medical care provided

- 1800s – Napoleondesignated vehicle and attendant to head to battle field

- 1860 – First recorded use of medic and ambulance use in the United States

- 1865 – First civilian ambulance, Commercial Hospital of Cincinnati, Ohio

- 1869 – First ambulance service, Bellevue Hospital in New York, NY

- 1899 – Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago operates automobile ambulance

EMS Between World War I and II

- 1900s – Hospitals place interns on ambulances, first real attempt at quality scene and transport care

- 1926 – Phoenix Fire Department enters EMS

- 1928 – First rescue squad launched in Roanoke, VA. Squad implemented by Julien Stanley Wise and named Roanoke Life Saving Crew

- 1940s

- Many hospital-based ambulance services shut down due to lack of manpower resulting from WWI

- City governments turn service over to police and fire departments

- No laws on minimum training

- Ambulance attendance became a form of punishment in many fire depts.

Post-World War II

- 1950s

- 1960s

- 1960 – LAFD puts medical personnel on every engine, ladder, and rescue company

- 1965 – “Accidental Death & Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society ” or The White Paper

- Lack of uniform laws and standards

- Ambulances and equipment of poor quality

- Communication lacking between EMS and hospital

- Training of personnel lacking

- Hospitals used part time staff in ED

- More people died in auto accidents than in Vietnam War

Star of Life

The DOT designed the Star of Life in 1973. The Staff of Asclepius (snaked wrapped around rod) represents the god of healing, and each point of the star represents one tenet of EMS. The DOT retains a trademark for this signal and has authorized its free use for vehicles and products related to EMS. Outside of the US, the Star of Life has been adopted by many countries to represent their emergency medicine. Today, it's a universally recognized symbol of hope across the globe.

The DOT designed the Star of Life in 1973. The Staff of Asclepius (snaked wrapped around rod) represents the god of healing, and each point of the star represents one tenet of EMS. The DOT retains a trademark for this signal and has authorized its free use for vehicles and products related to EMS. Outside of the US, the Star of Life has been adopted by many countries to represent their emergency medicine. Today, it's a universally recognized symbol of hope across the globe.- Detection: bystanders/first rescuers become aware of the problem

- Reporting: dispatch is activated

- Response: the first rescuers provide basic first aid

- On scene care: EMTs initiate care on site

- Care in transit: EMTs transport the patient to a hospital, providing treatment en route

- Transfer to definitive care: the patient is handed over to the hospital for specialized treatment

- 1966

- EMS Guidelines – Highway Safety Act, Standard 11

- Delivery of pre-hospital care using ambulances by Dr. Frank Pantridge in Belfast, Ireland

- 1967 -- AAOS creates “Emergency Care and Transportation of the Sick and Injured.” First textbook for EMS personnel

- 1968

- Task Force of the Committee of EMS drafts basic training standards, results in “Training of Ambulance Personnel and Others Responsible for Emergency Care of the Sick and Injured at the Scene and During Transport” by Dunlop and Associates

- American Telephone and Telegraph reserves 9-1-1 for emergency use

- 1969

- Dr. Eugene Nagel launches Nation’s first Paramedic program in Miami

- The Committee on Ambulance Design Criteria published “Medical Requirements for Ambulance Design and Equipment.”

- 1970s

- 1970

- Use of Helicopters in EMS explored

- National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians established

- 1971 -- The Committee on Injuries of the AAOS hosts national workshop on training for EMTs

- 1972

- Department of Health, Education and Welfare directed by President Nixon to develop new ways to organize EMS

- Departments of Defense and Transportation form helicopter evacuation service

- TV show “Emergency!” begins 8-year run

- 1973

- EMS Systems Act of 1973 passed

- Star of Life developed by DOT

- St. Anthony’s Hospital in Denver starts Nation’s first civilian aeromedical transport service

- 1974

- Department of Health, Education and Welfare published guidelines for developing and implementing EMS Systems

- Federal report discloses that less than half of ambulance personnel completed DOT 81-hour course

- 1975

- American Medical Association recognizes Emergency Medicine as specialty

- University of Pittsburgh and Nancy Caroline, M.D. awarded contract for first EMT-Paramedic National Standard Curriculum

- National Association of EMTs is formed

- 1970

- 1980s

- 1983 - The EMS for Children Act passed

- 1985 – National Association of EMS Physicians formed

- 1990s

- 1990 – The Trauma Care System Planning and Development Act is passed

- 1991 – The Commission on Accreditation of Ambulance Services sets standards and benchmarks for ambulances services

Sources

- The Ambulance: A History. Ryan Corbett Bell. McFarland, 2009.

- A History of Emergency Medical Services & Medical Transportation Systems in America. Robbins. 2005.

- EMS: A Historical Perspective, EMS Agenda for the Future. National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. NHTSA, 1996.

- History of Emergency Medical Services in the United States. Rockwood, Mann, Farrington, Hampton & Motley. The Journal of Trauma, 1976.

- The Revolutionary Flying Ambulance of Napoleon's Surgeon. Ortez. US Army Medical Department Journal, 1998.

- NHTSA instructional guide

- Bio of Jonathan Letterman